ABOUT

DANIEL GROS

Distinguished Fellow

Daniel Gros is a Member of the Board and Distinguished Fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS). He joined CEPS in 1986 and has been the Director of CEPS from 2000 to 2020. Prior to joining CEPS, Daniel worked at the IMF and at the European Commission as economic adviser to the Delors Committee that developed the plans for the euro.

Over the last decades, he has been a member of high-level advisory bodies to the French and Belgian governments and has provided advice to numerous central banks and governments, including Greece, the UK, and the US, at the highest political level.

Daniel is currently also an adviser to the European Parliament and was a member of the Advisory Scientific Council (ASC) of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) until June 2020. He held a Fulbright fellowship and was a visiting professor at the University of California at Berkeley in 2020.

Daniel holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago. He has published extensively on international economic affairs, including on issues related to monetary and fiscal policy, exchange rates, banking. He is the author of several books and editor of Economie Internationale and International Finance. He has taught at several leading European Universities and contributes a globally syndicated column on European economic issues to Project Syndicate.

laat ons niet twijfelen, niet aan de deskundigheid in de materie en zeker ook niet aan de onafhankelijkheid.

Seigniorage is the revenue the government obtains because the public holds zero interest-bearing debt in the form of cash and because the government can force commercial banks to hold reserves at zero interest.

dankzij het verkregen emissiemonopolie

over de macht beschikken om werkmiddelen in omloop te brengen waaraan geen enkele rentevergoeding noch enig renterisico verbonden is,

en op die manier over het economische voordeel beschikken om seigneuriagewinsten te kunnen realiseren.

Daniel Gros, in een IMF Working paper van 23 januari 1989 (International Monetary Fund – Research Department:

“Seigniorage in the EC: the implications of the EMS and financial market integration:

Seigniorage is the revenue the government obtains because the public holds zero interest-bearing debt in the form of cash and because the government can force commercial banks to hold reserves at zero interest or below market interest rates. The savings in interest payments on the stock of currency in circulation and required reserves can, from an economic point of view, be considered the implicit revenue from seigniorage.

The concept of seigniorage: Most academic discussions of seigniorage have tended to focus on the command over real resources the government can obtain by increasing the supply of fiat money, that is by printing currency in the form of bank notes and coins and using this currency to buy goods and services from the private sector.

Since fiat money can be viewed as a zero interest loan to the government the opportunity cost definition of the value of seigniorage is given the interest savings the government obtains by being able to issue zero interest rate securities in the form of currency.

Up to this point the discussion has focused on the role of the issuance of fiat money, however, most gevernments also impose obligatory reserve requirements on commercial banks which are usually calculated as a proportion of the total deposits held by the banks.

If no interest is paid on the balances the banks are required to hold with the central bank the economic nature of these required reserves is similar to that of currency: by increasing the amount of required reserves (for example by increasing the required reserve ratio) the government obtains an asset which can be used to acquire real resources.

First, why should commercial banks be remunerated for holding liquid reserves at the central bank? (…) Many economists today take for granted that bank reserves are remunerated. Yet this remunaration is a recent phenomenon. The ECB started this practice in 1999. Before 2000 the general practice was not to remunerate banks’ reserve balances.

It is difficult to find an economic justification for why bankers should be paid for holding liquidity while everybody else accepts not to be remunerated. The lack of economic foundation for paying interest on banks’ liquid reserves becomes even more striking when considering that central banks make profits because they have a monopoly from the state to create money.

The practice of paying interest to commercial banks amounts to transferring this monopoly profit to private institutions. This monopoly profit should in fact be returned to the government (the taxpayer) that has granted the monopoly rights. (..)

De Nationale Bank van België heeft het monopolie verkregen om het wettelijk betaalmiddel in omloop te brengen. Als een volledig geïntegreerd onderdeel van het Europees Stelsel van Centrale Banken (ESCB) deelt zij dit emissiemonopolie van de bankbiljetten in euro met de Europese Centrale Bank (ECB) en de andere Nationale Centrale Banken. Het is het ESCB welke de globale bankbiljettenomloop uitgeeft, en het is ook het Eurosysteem in zijn geheel welke de activa aanhoudt die de tegenpost zijn van die bankbiljettenomloop.

Het ESCB geeft, sedert haar oprichting, een rentevergoeding aan zowel de verplichte reserves als aan de deposito’s van de commerciële banken. De ECB heeft de keuze gemaakt om de macht verbonden aan het emissiemonopolie niet volledig aan te wenden. De seigneuriage die door het ESCB kan worden verdiend, volgens het Verdrag wordt berekend en via een stelsel van rentedragende vorderingen en verplichtingen wordt verdeeld over alle NCB’s) is dus functie van uitsluitend de globale bankbiljettenomloop: de ENIGE gratis en renterisico-loze werkmiddelen van het ESCB.

CEPS Policy Brief (N° 344 July 2016):

“ Negative rates and seigniorage: turning the central bank business model upside down? The special case of the ECB ”

Verhelderende inzichten:

Key points: (..) But many central banks are now earning a negative rate on their assets. Seigniorage, in fact, might now become negative in the euro area and in Japan.

The resulting profits should be regarded in the same way as those of investment banks. For the time being, central banks are making large profits on their investment banking activities, but little in terms of traditional seigniorage.

Printing bank notes when interest rates go negative becomes a loss-making business.

The seigniorage, or monetary income to be distributed among the NCB’s thus used to be (roughly) equal to cash in circulation multiplied with the euro area wide interest rate for lending operation set the ECB times. The ECB’s lending rate was set exactly to zero only in March of this year, which should lead to zero seigniorage revenues. (…) , the theoretical seigniorage revenues for the ECB might well turn negative this year.

Central banks as investment bankers:

The theoretical seigniorage revenues should thus disappear, and even become ever more negative with negative rates. (..) The reason is that as their traditional business model is destroyed by negative rates, central banks have gone in another business, namely maturity transformation of the kind usually done by investment banks. (…)

One should thus split the balance sheet of a central bank in two conceptually very different parts: 1) the issuing department (which issues legal tender), and 2) the investment banking department. (..)The revenues of the issuing department correspond to theoretical seigniorage: the interest rates multiplied by cash in circulation (required reserves on which interest is paid net out of the calculation).

The profits of the investment banking department are equal to the difference what the central bank pays in its liabilities (short term deposits of commercial banks) and what it earns on the securities it has invested in. The profits of the investment banking department are not certain. If the short term refinancing cost increase losse scan arise quickly

Wat Daniel Gros (CEPS en ex – Internationaal Monetair Fonds) in de feiten zegt over de situatie van de Nationale Bank van België, als een volledig geïntegreerd onderdeel van het ESCB:

Net zoals elke andere Nationale Centrale Bank van het ESCB is ook de Nationale Bank van België geëvolueerd van een klassieke emissiebank naar een werkelijke investeringsbank.

Het gaat hem hier niet over bepaalde “evoluties in het monetair instrumentarium”, maar puur om een bewuste keuze de gewenste investeringen niet langer te financieren hoofdzakelijk via renteloze (en renterisico-loze) werkmiddelen die haar bankbiljettenomloop is, doch wel via centrale bankreserves (reserveverplichtingen en deposito’s van commerciële banken), die wel een onbeperkte rentevergoeding en renterisico inhouden.

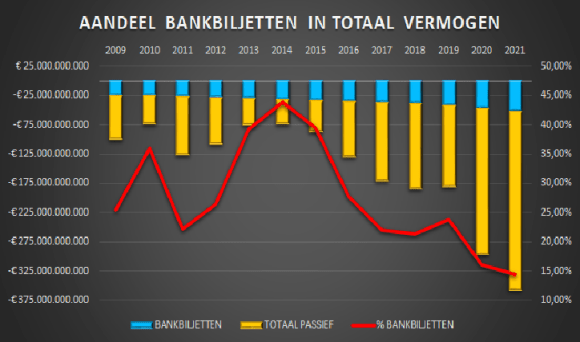

Het belang van de bankbiljettenomloop in het totaal van de financieringsmiddelen van de Nationale Bank van België daalt van 45% in boekjaar 2014 naar zo’n 15% in het boekjaar 2021.

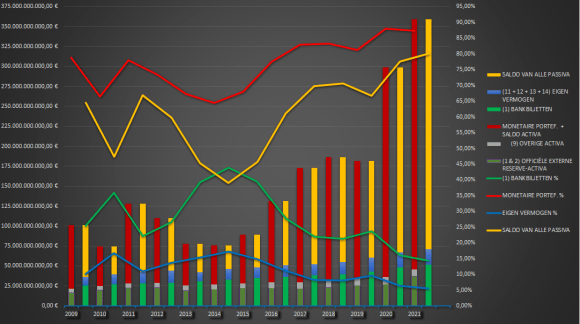

Voor elk boekjaar worden de activa en de passiva naast elkaar geplaatst. Het mag duidelijk zijn dat de sterke aangroei van de monetaire portefeuilles (de rode balkjes) nagenoeg volledig werd gefinancierd NIET via renteloze bankbiljetten (groene balkjes), doch WEL via de vergoede centrale bankreserves (oranje balkjes).

Naast de kredietrisico’s is vooral het gelopen renterisico over die (hoofdzakelijk) monetaire portefeuilles toegenomen, van een bedrag van zo’n 49 miljoen euro (eind boekjaar 2014) tot zo’n 314 miljard euro (eind boekjaar 2021).

De gemaakte financieringskeuzes spreken voor zich: einde boekjaar 2021 werd slechts 5% van de activa gefinancierd via het eigen vermogen (volgens de definitie van de ECB – de blauwe grafieklijn), 15% via de rente(risico-)loze bankbiljettenomloop (de groene grafieklijn) en niet minder dan 80% via hoofdzakelijk centrale bankreserves (gele grafieklijn) die een rentevergoeding op korte termijn krijgen.

In hindsight, it is clear that central banks made a colossal mistake in continuing massive bond-buying programs over the last few years.

De Belgische Wetgever heeft voor de winstbestemming van de Nationale Bank van België “een bijzondere relatie” voor de Belgische Staat gecreëerd: enerzijds ” de Nationale Bank van België – de Belgische Soevereine Staat” en anderzijds “de Nationale Bank van België – de aandeelhouders van de NBB (waaronder voor 50% de Belgische Staat). Tegelijkertijd heeft diezelfde Wetgever gewezen op een fundamenteel en altijd te respecteren onderscheid:

(..) Zonder afbreuk te doen aan het fundamentele onderscheid tussen de seigneuriage (de relatie centrale bank – soevereine Staat) en de vergoeding van het kapitaal (relatie Nationale Bank – aandeelhouders, inclusief, sinds 1948, de Staat), kan dan ook worden bevestigd dat het adequate karakter van de voorgestelde regeling voldoende is gegarandeerd. (..)

De memorie van Toelichting – DOC 52 . 1793/01 (pagina 7)

Mocht er een gesprek kunnen volgen tussen Daniel Gros en mezelf, omtrent alles wat hiervoor duidelijk werd gesteld, dan kunnen weinig andere conclusies worden getrokken:

- Gezien de Nationale Bank van België niet ten volle het voordeel verbonden aan het verkregen emissiemonopolie benut, en aan de verplichte reserves (en deposito’s) van de commerciële banken een door niets beperkte rentevergoeding toekent, waardoor de vennootschap zowel een belangrijke financiële kost als een onbeperkt krediet- en vooral renterisico op zich neemt, en

- Gezien alle financiële risico’s verbonden aan alle investeringen van de Nationale Bank van België worden gedragen (NIET met het vermogen van de gemeenschap maar WEL) met het eigen vermogen van de beursgenoteerde vennootschap (uiteindelijk toebehorend aan alle aandeelhouders) komen alle financiële resultaten (winst EN verlies) toe aan de bijzondere relatie “de Nationale Bank van België – de aandeelhouders van de NBB (waaronder de Belgische Staat voor 50%) “,

- Uitsluitend de winsten gerealiseerd door “het uitgiftedepartement” van de Nationale Bank van België kunnen als seigneuriagewinsten worden erkend. Alleen deze winsten zijn toe te rekenen tot de bijzondere relatie “Nationale Bank van België – de Belgische Soevereine Staat“.

Deze seigneuriage wordt berekend volgens de vastgelegde criteria en regels van de ECB, en wordt door de Regentenraad verdeeld tussen de vennootschap en de Belgische Soevereine Staat,- Daniel Gros stelt duidelijk dat ” de uitgiftedepartementen ” van de ECB en NCB’s van het ESCB (en dus ook van de Nationale Bank van België) sedert 2016 geen enkele euro seigneuriage meer verdienen. Dat de werkelijke en enige winstmotor die van ” de investeringsbanken ” zijn.

De Europese Centrale Bank bevestigt dit standpunt.